The Abandonment of Democracy

If democracy and human rights are high values, then all societies are not morally equal. This thought cuts sharply against Obama's multicultural sensibilities.

The most surprising thing about the first half-year of Barack Obama's presidency, at least in the realm of foreign policy, has been its indifference to the issues of human rights and democracy. No administration has ever made these its primary, much less its exclusive, goals overseas. But ever since Jimmy Carter spoke about human rights in his 1977 inaugural address and created a new infrastructure to give bureaucratic meaning to his words, the advancement of human rights has been one of the consistent objectives of America's diplomats and an occasional one of its soldiers.

This tradition has been ruptured by the Obama administration. The new president signaled his intent on the eve of his inauguration, when he told editors of the Washington Post that democracy was less important than "freedom from want and freedom from fear. If people aren't secure, if people are starving, then elections may or may not address those issues, but they are not a perfect overlay."

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton followed suit, in opening testimony at her Senate confirmation hearings. As summed up by the Post's Fred Hiatt, Clinton "invoked just about every conceivable goal but democracy promotion. Building alliances, fighting terror, stopping disease, promoting women's rights, nurturing prosperity—but hardly a peep about elections, human rights, freedom, liberty or self-rule."

A few days after being sworn in, President Obama pointedly gave his first foreign press interview to the Saudi-owned Arabic-language satellite network, Al-Arabiya. The interview was devoted entirely to U.S. relations with the Middle East and the broader Muslim world, and through it all Obama never mentioned democracy or human rights.

A month later, announcing his plan and timetable for the withdrawal of American forces from Iraq, the president said he sought the "achievable goal" of "an Iraq that is sovereign, stable, and self-reliant," and he spoke of "a more peaceful and prosperous Iraq." On democracy, one of the prime goals of America's invasion of Iraq, and one toward which impressive progress had been demonstrated, he was again silent.

While drawing down in Iraq, Obama ordered more troops sent to Afghanistan, where America was fighting a war he had long characterized as more necessary and justifiable than the one in Iraq. But at the same time, he spoke of the need to "refocus on Al Qaeda" in Afghanistan, at least implying that this meant washing our hands of the project of democratization there. The Washington Post reported that "suggestions by senior administration officials . . . that the United States should set aside the goal of democracy in Afghanistan" had prompted that country's foreign minister to make "an impassioned appeal for continued U.S. support for an elected government."

In early April, former New York Times correspondent Joel Brinkley summed up the administration's initial performance:

Neither President Obama nor Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has even uttered the word democracy in a manner related to democracy promotion since taking office more than two months ago. The State Department's Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor has put out 30 public releases, so far, and not one of them has discussed democracy promotion. Democracy, it seems, is banished from the Obama administration's public vocabulary.

At a glance, Obama's motives seemed readily apparent. Former State Department official J. Scott Carpenter observed that it was "obvious and understandable" that "the Obama administration wanted to distance itself from the tone and perceived baggage of the Bush administration." But there were two reasons why this explanation did not satisfy.

For one, Obama might have put his own stamp on the issue without turning so sharply away from the goals of human rights and democracy. In 1981, Ronald Reagan came to the presidency with a mandate analogous to Obama's, namely, to undo the works of an unpopular predecessor. At first, Reagan was inclined to eschew human rights as just another part of Jimmy Carter's wooly-minded liberalism. In an early interview, Secretary of State Alexander Haig announced that the Reagan administration would promote human rights mostly by combating terrorism. But soon Reagan had second thoughts: instead of jettisoning the issue, he put his own distinctive spin on it by shifting the rhetoric and the program to focus more on fostering democracy.

In a similar vein, Obama could have faulted the Bush administration for its ineffectiveness in promoting democracy and promised that his own team would do it better. Indeed, Michael McFaul, who handled democracy issues in the Obama campaign, declared after the election that the new administration would "talk less and do more" about democratization than Bush had done. But when McFaul was appointed to the National Security Council staff, he was given the Russia portfolio rather than the job of overseeing democracy promotion. The latter task, which had been entrusted to senior staff during the Bush years, was given to no one.

The other reason why Obama's tack cannot be understood merely by his impulse to be unlike Bush is that his disinterest in democracy and human rights is global. The idea of promoting these values did not originate with Bush but with Carter and Reagan, reinforced by Bill Clinton. Bush's innovation was to apply this to the Middle East, which heretofore largely had been exempted. Repealing Bush's legacy would have meant turning the clock back on America's Middle East policy. But Obama scaled back democracy efforts not only there; he did it everywhere.

Thus for example, Clinton, on a first state visit to China, told reporters she would not say much about human rights or Tibet because "our pressing on those issues can't interfere with the global economic crisis, the global climate change crisis and the security crisis." Amnesty International declared it was "shocked and extremely disappointed" by her words. Unfazed, Clinton moved on to Russia, where she glibly presented its dictator, Vladimir Putin, with a toy "reset button" even while the string of unsolved murders of independent journalists that has marked his reign continued to lengthen.

To be sure, China and Russia are powerful countries with which Washington must do business across a range of issues, and because of their importance, all U.S. administrations have been guilty of unevenness in lobbying them to respect human rights. However, the Obama administration has downplayed human rights not only with the likes of Beijing and Moscow but also with weak countries whose governments have no leverage over America.

For example, Clinton ordered a review of U.S. sanctions against the military dictatorship of Burma because they haven't "influenced the Burmese government." This softening may have emboldened that junta to place opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi on trial in May after having been content to keep her under house arrest most of the last eighteen years. The government of Sudan is even weaker and more of an international pariah than Burma's, but the Obama administration also let it be known that it was considering easing Bush-era sanctions applied against Khartoum in response to the campaign of murder and rape in Darfur. According to the Washington Post:

Many human rights activists have been shocked at the administration's apparent willingness to consider easing sanctions on Burma and Sudan. The Obama presidential campaign was scornful of Bush's handling of the killings in Sudan's Darfur region, which Bush labeled as genocide, but since taking office, the administration has been caught flat-footed by Sudan's recent ousting of international humanitarian organizations.

While it is hard to see any diplomatic benefit in soft-pedaling human rights in Burma and Sudan, neither has Obama anything to gain politically by easing up on regimes that are reviled by Americans from Left to Right. Even so ardent an admirer of the President as columnist E. J. Dionne, the first to discern an "Obama Doctrine" in foreign policy, confesses to "qualms" about "the relatively short shrift" this doctrine "has so far given to concerns over human rights and democracy."

Whether or not there is something as distinct and important as to warrant the label "doctrine," the consistency with which the new administration has left aside democracy and human rights suggests this is an approach the president has thought through. Following his meeting with the Organization of American states in April, Obama told a press conference: "What we showed here is that we can make progress when we're willing to break free from some of the stale debates and old ideologies that have dominated and distorted the debate in this hemisphere for far too long." His secretary of state echoed the thought: "Let's put ideology aside," she said. "That is so yesterday."

his begs the question of exactly which ideologies are passé or whether all are equally so. Communism, which so roiled the twentieth century, is certainly on its deathbed. Democracy, on the other hand, has flourished and spread in recent decades as never before, to the point where more than sixty percent of the world's governments are chosen in bona fide elections. To lump together these "ideologies" is gratuitously to belittle democracy.

Obama seems to believe that democracy is overrated, or at least overvalued. When asked about the subject in his pre-inaugural interview with the Washington Post, Obama said that he is more concerned with "actually delivering a better life for people on the ground and less obsessed with form, more concerned with substance." He elaborated on this thought during his April visit to Strasbourg, France:

We spend so much time talking about democracy—and obviously we should be promoting democracy everywhere we can. But democracy, a well-functioning society that promotes liberty and equality and fraternity, does not just depend on going to the ballot box. It also means that you're not going to be shaken down by police because the police aren't getting properly paid. It also means that if you want to start a business, you don't have to pay a bribe. I mean, there are a whole host of other factors that people need . . . to recognize in building a civil society that allows a country to be successful.

Whether or not the President was aware of it, he was echoing a theme first propounded long ago by Soviet propagandists and later sung in many variations by all manner of Third World dictators, Left to Right. It has long since been discredited by a welter of research showing that democracies perform better in fostering economic and social well being, keeping the peace, and averting catastrophes. Never mind that it is untoward for a President of the United States to speak of democracy as a mere "form," less important than substance.

The trend of downgrading democracy and human rights has already been evident in some important actions abroad. When Venezuela's would-be dictator, Hugo Chavez, held a referendum to set aside the country's long tradition of presidential term limits, the U.S. government went out of its way to endorse the process. The Associated Press reported:

The Obama administration says the referendum that cleared the way for Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez to run for re-election was democratic. It was rare praise for a U.S. antagonist after years of criticism from the Bush administration. U.S State Department spokesman Gordon Duguid noted "troubling reports of intimidation." But he added Tuesday that "for the most part this was a process that was fully consistent with democratic process."

While focusing on lack of irregularities in the polling, this response studiously ignored the larger issue. Term limits have been a pillar of democracy across Latin America, where there is a lamentable history of elected leaders holding onto office by unscrupulous means.

However punctilious the procedure, this constitutional maneuver on the part Chavez, who makes no secret of his ambition to serve as president for life, posed a dire threat to the preservation of democracy in that country.

Perhaps the clearest shift in U.S. policy has been toward Egypt. By far the largest of the Arab states, and the most influential intellectually, Egypt has also been the closest to Washington. Thus, the Bush administration's willingness to pressure the government of Hosni Mubarak was an earnest sign of its seriousness about democracy promotion.

For their part, Egyptian reformers urged the U.S. to make its aid to Egypt conditional on reforms. The Bush administration never took this step, but the idea had support in Congress, and it hung like a sword over the head of Mubarak's government. Obama has removed the threat. As the Associated Press reported: "Egypt's ambassador to the U.S., Sameh Shukri, said last week that ties are on the mend and that Washington has dropped conditions for better relations, including demands for 'human rights, democracy and religious and general freedoms.'"

"Conditionality" with Egypt "is not our policy," Secretary of State Clinton said in an interview with Egyptian TV earlier this month. "We also want to take our relationship to the next level."

While promising unimpeded assistance to the regime, the Obama administration backed away from aiding independent groups, something the Bush administration had insisted on doing despite objections from the authorities. Announcing the elimination of programs directly supporting Egyptian civil-society organizations, the U.S. ambassador, Margaret Scobey, explained that this would "facilitate" smoother relations with the Egyptian government. The New York Times summarized the Obama administration's steps:

The White House has accommodated President Mubarak by eliminating American funding for civil society organizations that the state refuses to recognize, and by stating publicly that neither military nor civilian funding will be conditioned on reform. This has provoked alarm from liberals, from scholarly experts and from activists in the region.

As the popular young Egyptian blogger, "Sandmonkey," irrepressibly irreverent and scatological, put it: "Let's face it, [Obama] ain't going to push on human rights and democracy. That era is gone. We are all about diplomacy and friendship now, and that's what the American people want, even if the price is that the democracy activists in Egypt get f—ed."

This formed the backdrop to the president's much-anticipated speech to the Muslim world delivered in Cairo on June 4. Of the many thorny issues he was expected to address, the setting necessitated that he spell out his views on democracy and human rights in Middle East more explicitly than before. In the New York Times, James Traub formulated the question this way:

Egypt was the central target of President Bush's Freedom Agenda . . . . But when an opposition Islamist party did well at the polls, Egypt's security apparatus cracked down. The Bush administration, concerned about pushing a key ally too far, responded meekly. . . . President Obama's words in Cairo are presumably being framed in the context of that episode. Should Mr. Bush have pushed harder for democratic reform in Egypt and with other allies? Should his administration have spoken more softly, less publicly? Should he, like his father, have devoted less attention to the way regimes treat their citizens, and more to winning cooperation on America's national security objectives?

In the speech, Obama tackled the issue head-on, making "democracy," "religious freedom," and "women's rights" three of the seven "specific issues" that he said "we must finally confront together." On democracy, he spoke with eloquence:

All people yearn for certain things: the ability to speak your mind and have a say in how you are governed; confidence in the rule of law and the equal administration of justice; government that is transparent and doesn't steal from the people; the freedom to live as you choose. These are not just American ideas; they are human rights. And that is why we will support them everywhere.

Strong as this was, its ultimate import remained elusive. Obama followed these words immediately with the caveat that "there is no straight line to realize this promise." And while he asserted his belief in "governments that reflect the will of the people," he added, "Each nation gives life to this principle in its own way, grounded in the traditions of its own people. America does not presume to know what is best for everyone."

This, alas, is very much the claim advanced by many authoritarian regimes, including the absolute monarchy of Saudi Arabia, which Obama had visited the day before. Nowhere did the president make the critical point that elections are the only known way to determine the will of the people. That, apparently, would have been "presumptuous."

When he turned to women's rights, Obama's strongest words were that women should be educated and free to choose whether or not to live in a traditional manner. Here, too, he was at pains to avoid sounding as if America had a worthier record than the nations he was addressing or had something to teach them. To the contrary: "Women's equality [is] by no means simply an issue for Islam. In Turkey, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, we've seen Muslim-majority countries elect a woman to lead. Meanwhile, the struggle for women's equality continues in many aspects of American life, and in countries around the world."

At three different points in the speech, Obama defended a woman's right to wear the hijab, apparently as against the restrictions in French public schools or Turkish government offices or perhaps in the U.S. military, which insists on uniform headgear. But he said not a word about the right not to wear head covering, although the number of women forced to wear religious garments must be tens of thousands of times greater than the number deprived of that opportunity. This was all the more strange since he had just arrived from Saudi Arabia, where abbayas—head-to-toe cloaks put on over regular clothes—are mandatory for women whenever they go out. During Obama's stop in Riyadh the balmy spring temperature was 104 degrees; in the months ahead it will be twenty or thirty degrees hotter. The abbayas must be black, while the men all go around in white which, they explain, better repels the heat.

Nor did Obama mention either directly or indirectly that all Saudi women are required to have male "guardians," who may be a father, husband, uncle or brother or even a son, without whose written permission it is impossible to work, enroll in school or travel, or that they may be forced into marriage at the age of nine. Speaking on women's rights in Egypt, he might—but did not—also have found something, even elliptical, to say about genital mutilation, which is practiced more in that country than almost anywhere else.

On religious freedom, Obama invoked Islam's "proud tradition of tolerance." In one of his more prodding passages, he declared that "the richness of religious diversity must be upheld—whether it is for Maronites in Lebanon or the Copts in Egypt." One of the two institutions co-hosting his speech was Al-Azhar University, which Obama saluted in his opening paragraph as "a beacon of Islamic learning." This may be so, but Al-Azhar admits only Muslims. Foreign as well as native adherents to the message of the Prophet may attend, but Egyptian Christians are excluded. Perhaps this could be understood if it were only a school of Islamic learning (although, even then, why?), but today Al-Azhar offers degrees in medicine, engineering, and a panoply of subjects. Its tens of thousands of students are subsidized by state funds provided by Egyptian taxpayers, ten percent of whom are Copts, barred from Al-Azhar.

In these passages, as throughout the speech, Obama's method was to induce his audience to swallow a few perhaps-unwelcome truths by slathering them over with a thick sauce of soothing half-truths, distortions, omissions and false parallels.

Thus, the Cairo oration was a culmination of the themes of Obama's early months. He had blamed America for the world financial crisis, global warming, Mexico's drug wars, for "failure to appreciate Europe's role in the world," and in general for "all too often" trying "to dictate our terms." He had reinforced all this by dispatching his Secretary of State on what the New York Times dubbed a "contrition tour" of Asia and Latin America. Now he added apologies for overthrowing the government of Iran in 1953, and for treating the Muslim countries as "proxies" in the Cold War "without regard to their own aspirations."

Toward what end all these mea culpas? Perhaps it is a strategy designed, as he puts it, to "restor[e] America's standing in the world." Or perhaps he genuinely believes, as do many Muslims and Europeans, among others, that a great share of the world's ills may be laid at the doorstep of the United States. Either way, he seems to hope that such self-criticism will open the way to talking through our frictions with Iran, Syria, China, Russia, Burma, Sudan, Cuba, Venezuela, and the "moderate" side of the Taliban.

This strategy might be called peace through moral equivalence, and it finally makes fully intelligible Obama's resistance to advocating human rights and democracy. For as long as those issues are highlighted, the cultural relativism that laced his Cairo speech and similar pronouncements in other places is revealed to be absurd. Straining to find a deficiency of religious freedom in America, Obama came up with the claim that "in the United States, rules on charitable giving have made it harder for Muslims to fulfill their religious obligation." He was referring, apparently, to the fact that donations to foreign entities are not tax deductible. This has, of course, nothing to do with religious freedom but with assuring that tax deductions are given only to legitimate charities and not, say, to "violent extremists," as Obama calls them (eschewing the word "terrorist").

Consider this alleged peccadillo of America's in comparison to the state of religious freedom in Egypt, where Christians may not build, renovate or repair a church without written authorization from the President of the country or a provincial governor (and where Jews no longer find it safe to reside). Or compare it to the practices at the previous stop on Obama's itinerary, Saudi Arabia, where no church may stand, where Jews were for a time not allowed to set foot, and where even Muslims of non-Sunni varieties are constrained from building places of worship.

In short, while it may be possible to identify derogations from democracy and human rights in America, those that are ubiquitous in the Muslim world are greater by many orders of magnitude. If democracy and human rights are held as high values, then all societies are not morally equal. This is a thought that cuts sharply against Obama's multicultural sensibilities.

America not only embodies these values, it is also more responsible than any other country for their spread. Many peoples today enjoy the blessings of liberty thanks to the influence of the United States, thanks to its aid, its example, and its leading role in bringing down the Axis powers, the Soviet Union and European colonialism. Moreover, the advancement of human rights and democracy requires the exercise of American influence and in turn may serve to strengthen that influence—neither of these, it seems, processes to be welcomed by apostles of national self-abnegation.

In Cairo, once again, President Obama criticized the Bush administration for having acted "contrary to our ideals" when it infringed rules of due process in the course of the war against terror and authorized "enhanced interrogation techniques" that many believe are tantamount to torture. At worst, these infringements were bad answers to questions to which there were no good ones. Some of these practices may have been wrong, but there has not been a single serious allegation that any official employed them for any ulterior purpose, that is, for anything other than the goal of protecting our country in a time of war and national peril.

To dwell on this subject, as Obama has done, is to place great emphasis on humane values. How odd, then, to remove human rights and democracy from the agenda of our foreign policy. This is not the place to enter the debate about torture, but even if Khaled Sheikh Mohammed—the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks who was the main victim of waterboarding—and others were abused, there is little doubt that they were up to evil. It is hard to understand vociferating over their treatment even while silencing America's voice on behalf of such brave liberals as Ayman Nour and Sa'ad Edin Ibrahim, persecuted by the government that hosted Obama in Cairo for the peaceful advocacy of democracy. In this can be found neither strategic nor moral coherence.

Joshua Muravchik is a fellow at the Foreign Policy Institute of the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. His new book, The Next Founders: Voices of Democracy in the Middle East, has just been released by Encounter.

If the Obama administration were a flotilla of ships, it might be sending out an SOS right about now. ObamaCare has hit the political equivalent of an iceberg. And last week the president’s international prestige was broadsided by the Scots, who set free the Lockerbie bomber without the least consideration of American concerns. Mr. Obama’s campaign promise of restoring common sense to budget management is sleeping with the fishes.

If the Obama administration were a flotilla of ships, it might be sending out an SOS right about now. ObamaCare has hit the political equivalent of an iceberg. And last week the president’s international prestige was broadsided by the Scots, who set free the Lockerbie bomber without the least consideration of American concerns. Mr. Obama’s campaign promise of restoring common sense to budget management is sleeping with the fishes.

![[Federation Feature]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-AY282_logo_c_20080122162821.gif)

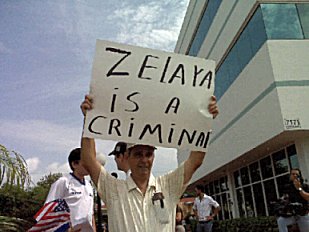

![[Honduran Officials Defend Coup]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-DY847_0629ho_F_20090629174129.jpg) Associated Press

Associated Press

![[SB124630407694469631]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-DY765_0629ho_D_20090629154745.jpg)

![[THE AMERICAS]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/ED-AJ748_amcol0_D_20090628115958.jpg) Associated Press

Associated Press