7 Potential Economic Effects Of A War With Iran

As each day passes, war in the Middle East seems increasingly likely. The truth is that Israel will never allow Iran to develop nuclear weapons, and Iran is absolutely determined to continue developing a nuclear program. So right now Israel and Iran are engaged in a really bizarre game of "nuclear chicken" and neither side is showing any sign of blinking. In fact, even prominent world leaders are now openly stating that it is basically inevitable that Israel is going to strike Iran. For example, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi recently made the stunning admission that the G8 nations "absolutely believe" that Israel will attack Iran. But a conflict between Israel and Iran would not just affect the Middle East - it would have staggering implications for the rest of the globe.

As each day passes, war in the Middle East seems increasingly likely. The truth is that Israel will never allow Iran to develop nuclear weapons, and Iran is absolutely determined to continue developing a nuclear program. So right now Israel and Iran are engaged in a really bizarre game of "nuclear chicken" and neither side is showing any sign of blinking. In fact, even prominent world leaders are now openly stating that it is basically inevitable that Israel is going to strike Iran. For example, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi recently made the stunning admission that the G8 nations "absolutely believe" that Israel will attack Iran. But a conflict between Israel and Iran would not just affect the Middle East - it would have staggering implications for the rest of the globe.

So just what would a war between Israel and Iran mean for the world economy?

The following are 7 potential economic effects of a conflict between Israel and Iran....

#1) The Price Of Oil Would Skyrocket - One of the very first things a war with Iran would do is that it would severely constrict or even shut down oil shipments through the Strait of Hormuz. Considering the fact that approximately 20% of the world’s oil flows through the Strait of Hormuz, world oil markets would instantly be plunged into a frenzy. In fact, some analysts believe that oil prices would rise to $250 per barrel.

So are you ready to pay 8 or 10 dollars for a gallon of gasoline? What do you think that would do to the U.S. economy?

The truth is that every single transaction that we make every single day is influenced by the price of oil. If the price of oil suddenly doubles or triples that would absolutely devastate the already very fragile U.S. economic system.

#2) Fear Would Explode In World Financial Markets - Even without a war, the dominant force in world financial markets in 2010 is fear. We are already seeing unprecedented volatility in financial markets around the globe, and there is nothing like a war to turn fear into a full-fledged panic. And what happens when panic grips financial markets? What happens is that they crash.

#3) World Trade Would Instantly Seize Up - Once upon a time the economies of the world were relatively self-contained, so a war in one area would not necessarily wreck economies all over the globe. But all of that has changed now. Today, the economies of virtually every nation are highly interdependent. That has some advantages, but it also has a lot of disadvantages.

If a war with Iran did break out, nations all over the globe would start taking sides and world trade would seize up. The global flow of goods and services would be severely interrupted. That would be enough to push many nations around the world into a full-blown depression.

#4) Military Spending Would Escalate - Even if the United States was not pulled directly into a conflict between Israel and Iran, there is little doubt that the U.S. would be spending a lot of money and resources to support Israel and to build up military assets in the region in case a wider war broke out. The U.S. has already spent somewhere in the neighborhood of a trillion dollars on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. If war does break out with Iran the amount of money the U.S. government could be forced to spend could be absolutely staggering.

The truth is that the U.S. is already drowning in debt. At this point the U.S. government is over 13 trillion dollars in debt, and another Middle East war is certainly not going to help things.

#5) Russia Would Greatly Benefit - Russia and other major oil producers outside of the Middle East would greatly benefit if a war with Iran erupts. Russia is already the number one oil producer in the world, and if supplies out of the Middle East were disrupted for any period of time it would mean an unprecedented windfall for the Russian Bear.

#6) Massive Inflation - A huge jump in the price of oil and dramatically increased military spending by the U.S. government would most definitely lead to price inflation. We would probably see a dramatic rise in interest rates as well. In fact, it is quite likely that if a war with Iran does break out we would see a return of "stagflation" - a situation where prices are rapidly escalating but economic growth as a whole is either flat or declining.

#7) The Price Of Gold Would Go Through The Roof - When there is a high degree of uncertainty in world financial markets, where do investors turn? As we have seen very clearly recently, they turn to gold. As high as the price of gold is now, the truth is that it is nothing compared to what would happen if a war with Iran breaks out. When times get tough, we almost always see a flight to safety. Right now none of the major currencies around the globe provide much safety, so investors are increasingly viewing precious metals such as gold and silver as a wealth preservation tool.

War is never pleasant. If war with Iran does break out it could potentially set off a chain of cascading events that would permanently alter the world economy for the rest of our lifetimes.

So let us hope that war does not erupt. It wouldn't be good for anyone. But the reality is that at this point it almost seems like a foregone conclusion. Tensions in the Middle East are rising by the day, and all sides are certainly preparing as if they fully expect a war to happen.

Even without a war with Iran, incredibly hard economic times are on the way, so if a war does happen it could mean a complete and total economic disaster.

So what do you think? Will a war with Iran devastate the world economy? Feel free to leave a comment with your opinion....

New Yorker Magazine's Pathetic Attack

New Yorker Magazine's Pathetic Attack on Heroic Freedom Fighter Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Ayaan Hirsi Ali is an ex-Muslim who is guarded round-the-clock because of Islamic jihadist threats to murder her. She is also a fearless champion of human rights and especially the rights of women who suffer under the institutionalized discrimination mandated for them by Islamic law.

The New Ideological Divide

The New Ideological Divide: Stimulators vs Austereians

Economies do not grow because consumers spend; consumers spend because economies grow.

Despite the apparent deficit-cutting solidarity that emerged from this weekend's G-20 meeting in Toronto, it is clear that the great powers of the industrialized world have not been this philosophically estranged since the end of the Cold War. Ironically, in this new contest, the former belligerents have switched sides - the capitalists are now the socialists, and vice versa.

We now are witnessing a struggle between two camps that I playfully call the "Stimulators" and the "Austereians." Both warn that a worldwide depression will ensue if governments now make the wrong choices: the Stimulators say the danger lies in spending too little and the Austereians from spending too much. Each side also has their own economic champion: the Stimulators follow the banner of Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman, while the Austereians are forming up behind the recently reformed former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan. (It is cold comfort to witness "The Maestro" belatedly returning to the hard-money positions that characterized his earlier years.)

In a recent Wall Street Journal editorial, Greenspan argued that the best economic stimulus would be for the world's leading debtors (the United States, UK, Japan, Italy, et al) to rein in their budget deficits, a strategy dubbed "austerity" by the press. Greenspan explains that because lower deficits will restore confidence, diminish the threat of inflation, and allow savings to flow to private-sector investment rather than public-sector consumption, the short-term pain will lead to gains both in the mid- and long-term. Rather than redistributing a shrinking pie, this approach allows the pie to grow. Greenspan's Austereian view has been echoed loudly in the highest policy circles of Berlin, Ottawa, Moscow, Beijing, and Canberra.

Meanwhile, in several articles for his New York Times column, including one today, Krugman has argued that those who push for austerity in the face of recession are either doing so for political expediency or out of a "crazy" fealty to archaic economic views. Krugman has apparently judged inadequate the trillions of dollars worth of deficit spending unleashed by the United States and European governments in the last 24 months. He believes our only remedy is to spend more - no matter how much debt results. Absent this, he claims, millions of workers "will never work again." Unfortunately, Washington has clearly aligned itself with Krugman and the Stimulators.

Reading straight from the Keynesian playbook, Krugman argues that cutting government spending now will simply send the economy back into recession. He asserts that by flooding the economy with money, i.e. "stimulus," governments can encourage consumers to spend. Once the spending creates better conditions, so the argument goes, the economy will be better positioned to withstand the spending cuts, tax hikes, and higher interest rates necessary to address the staggering deficits left behind.

Krugman proposes an enticing argument that is nevertheless built on rubbish. Economies do not grow because consumers spend; consumers spend because economies grow [for a detailed explanation of how this works, read my latest book: How an Economy Grows]. Investment capital comes from savings, and when governments borrow, savings are diverted from private investment. While it is possible for governments to invest as well, it is much more likely that the money will be spent on entitlements or "invested" in projects that may be politically advantageous but economically useless.

Any money spent by governments is not available to the private sector to invest. The Stimulators don't make this connection because they believe money grows on trees and that a printing press is a legitimate creator of wealth. However, printing money merely encourages people to spend their savings now rather than wait for it to lose value through inflation. This is okay to Stimulators, because stimulating "demand" by any means necessary is the only goal they can see.

What really grows an economy is not more demand, but more supply [also explained in my book]. The Austereian argument is that reductions in government spending will allow the private sector to generate the additional supply of goods and services. Europe seems to understand this; unfortunately, the US does not. Judging by the recent weakness of the dollar - not only against gold, but other fiat currencies, including the pound and the euro - the markets are coming to the same conclusion.

As sovereign-debt worries initially spread throughout Europe, the dollar benefitted. However, now that Europe has demonstrated a willingness to reduce its debts, while we have committed to make ours even larger, the sovereign-debt worries are moving west.

If Greenspan and the Austereians are correct, the stimulus will fail and leave us in a much deeper hole. As long as governments create bigger deficits, we will never have a sustainable recovery. Instead, we will be chasing our tail, and wearing ourselves out in the process. When we finally realize the folly of this approach, the austerity measures that we will then be forced to adopt will make those currently proposed by the Europeans seem relatively painless.

My guess is that before year-end, our stimulus-induced recovery will falter, prompting Obama and Congress to administer even more stimulus. After all, the Stimulators have no other answer. However, given the adverse reaction this will produce in the currency and debt markets, this next jolt will likely vindicate the Austereians, as the world witnesses its greatest power careen into inflationary depression.

If global jihad isn’t the enemy, what is?

If global jihad isn’t the enemy, what is?

By BOAZ GANORIn fact, those pesky terms like “Islamist,” “jihadist” and even “terrorism” don’t seem to fit in his vision of a US security strategy at all, a point that was made clear late last month with the release of Obama’s new National Security Strategy (NSS) document.

Keeping religious rhetoric out of the document – and out of the NSS in general – may indeed soften the image of the US in the Muslim world. But it may also be the source of the strategy’s ultimate and inevitable failure.

The public got a preview of the strategy’s key points during a presentation by John Brennan, assistant to the president for homeland security and counterterrorism, at an event hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies last month.

Brennan outlined the president’s new strategic approach to the threats of terrorism facing the US, laying out two primary challenges: first, “the immediate near-term challenge of destroying al-Qaida and its allies...,” and second, “the longer-term challenge of confronting violent extremism generally.”

Disconcertingly, the subsequent doctrine presented by Brennan, designed by the Obama administration to address those two challenges, seems to be based on inaccurate, inconsistent and even misleading assumptions.

The most troubling statements made by Brennan related to his very definition of the enemy itself; he argued that the war being fought by the US is not against “terrorism,” because “terrorism is but a tactic.”

Nor, he argued, should it be described as a war against “jihadists” or “Islamists,” because “jihad is holy struggle, a legitimate tenet of Islam meaning to purify oneself of one’s community.”

So who is the enemy of the US, according to the president’s number one consultant on counterterrorism? Simple. “Al-Qaida and its terrorist affiliates.” Brennan and the Obama administration have essentially taken the complicated, multifaceted security threat posed by the global jihad movement and oversimplified it, making it seem that the challenge is limited to dealing with the nucleus of al-Qaida and its secluded affiliates.

These terrorists, according to Brennan’s argument, seem to have nothing in common.

They are not Islamist in nature; they are not jihadists. He argues that they have nothing to do with Islam. They can hardly even be described as terrorists, since terrorism is not the US’s enemy. They are just a bunch of villains that happen to hate the US and despise its liberal and democratic values.

According to this logic, it seems the US will once again be secured once Obama manages to smoke them out of their caves and eliminate them.

TO COMPREHEND the full scope of fallacies being adopted by the administration in its references to counterterrorism, we should borrow a metaphor from the medical world.

Many scholars and decision makers have referred to international and local terrorism as a cancer. Today the worst form of international terrorism is global jihadi terrorism, with al-Qaida at its epicenter. Global jihadi terrorism is the metastatic cancer of the 21st century – a disease that spreads from one organ or body part to another. This is a cancer that has spread all over the Muslim world – from Arab and Muslim countries to Muslim communities in Western countries.

This is not meant to imply that the body of Islam itself is constructed of cancer cells, or that the majority of the cells of this body are infected. Just the opposite. The body is otherwise healthy; most of these cells are productive, functioning and serve a positive end.

Nevertheless, this body of Islam is suffering from a severe disease – the metastasis of global jihadi cancer.

There are four possible treatments to this disease.

One is chemotherapy. The Obama administration perceives president Bush’s counterterrorism doctrine as a counterproductive and overly intrusive treatment that poisons the whole body while trying to get rid of the cancer cells.

What Obama’s administration fails to understand is that, unfortunately, one can’t treat a metastatic cancer that has spread all over the body only with focused radiation or even a surgery. His doctrine not only turns a blind eye to the nature and the severity of the disease, but it also refuses to acknowledge the fact that the Muslim world indeed has a problem. The administration ignores the fact that the tactic of global jihadi terrorism and the birth of al-Qaida and its affiliates is a result of extreme radical Islamic indoctrination – religious indoctrination.

The administration refuses to acknowledge the need to contend with an extremist interpretation of Islam that calls for the killing of “infidels” – i.e., anyone who does not hold its extreme miscalculated interpretation of Islam. The administration is deluding itself and misleading the American people to believe that this is a limited, concrete problem that can be solved if only al-Qaida and its affiliates are defeated.

As Brennan put it, “Describing our enemy in religious terms would lend credence to the lie propagated by al-Qaida and its affiliates to justify terrorism, that the United States is somehow at war against Islam.” Brennan tends to forget or even intentionally prefers to ignore the severity and the complexity of the threat of this global jihadi cancer. Moreover, he is not even ready to acknowledge that there is an illness in the body of Islam – that there is a religious nature to this threat.

Without calling a spade a spade, the Obama administration will find itself dealing with the negligible symptoms but will not find the needed cure for the disease.

IT SEEMS that both the Bush and Obama administrations overlooked the only real cure – the need to develop a strong autoimmune response within the Muslim body, with healthy cells designed to attack the body’s own diseased cells.

The only solution to the global jihadi threat is a Muslim counterreaction. Only Muslims can educate Muslims. Only Muslims can prevent global jihadists from seducing their constituencies and buying their hearts and minds. Only Muslims can save Islam from militant Islamists. But unfortunately, many Muslims ignore their responsibility.

They believe that this is a phase that will run its course, a wave that will recede with the tide. Many are not brave enough to take a stand against this dangerous and negative trend gripping the Muslim World.

The US will not be able to motivate Muslims and promote the necessary autoimmune reaction with policies of appeasement, nor will Islamophobic doctrines be successful. The US must look straight into the eyes of those in the Muslim world and say the following: Dear friends, you have an enormous problem. You are suffering from a fatal illness. There is only one cure for your disease – you need to identify and neutralize these bad seeds, these diseased cells – the metastatic cancer cells of global and local jihad. You need to save your body and soul, your prestige, your culture and your religion and prevent the deterioration of Islam to the dark days of illiteracy, militancy, hate and suffering. It is your responsibility to save Islam from the Islamists, and we will always be there for you and support you in this crucial campaign.

You should not waste your efforts by telling us that Islam is the religion of peace and clemency, and that jihad is all about good deeds and charity. We believe you. Your task, however, is to teach those violent Islamists – those who are beheading innocent civilians and blowing up weddings, schools and kindergartens in the name of Islam and under the flag of jihad – that their actions do not promote or honor Islam, nor do they fulfill the obligation of jihad. This is a misinterpretation of Islam that humiliates the whole religion and degrades the great Muslim people wherever they are.

We can put rhetoric aside, but let’s not sacrifice or undermine our understanding of the threat while we do so.

The writer is founder and executive director of ICT – The International Policy Institute for Counterterrorism, and deputy dean of the Lauder School of Government at the Interdisciplinary Center, Herzliya (IDC).

Empowering Workers: The Privatization of Social Security in Chile

Empowering Workers: The Privatization of Social Security in Chile – by José Piñera

A specter is haunting the world. It is the specter of bankrupt state-run pension systems. The pay-as-you-go pension system that has reigned supreme through most of this century has a fundamental flaw, one rooted in a false conception of how human beings behave: it destroys, at the individual level, the essential link between effort and reward — in other words, between personal responsibilities and personal rights. Whenever that happens on a massive scale and for a long period of time, the result is disaster.

A specter is haunting the world. It is the specter of bankrupt state-run pension systems. The pay-as-you-go pension system that has reigned supreme through most of this century has a fundamental flaw, one rooted in a false conception of how human beings behave: it destroys, at the individual level, the essential link between effort and reward — in other words, between personal responsibilities and personal rights. Whenever that happens on a massive scale and for a long period of time, the result is disaster.

Two exogenous factors aggravate the results of that flaw: (1) the global demographic trend toward decreasing fertility rates; and, (2) medical advances that are lengthening life. As a result, fewer and fewer workers are supporting more and more retirees. Since the raising of both the retirement age and payroll taxes has an upper limit, sooner or later the system has to reduce the promised benefits, a telltale sign of a bankrupt system.

Whether this reduction of benefits is done through inflation, as in most developing countries, or through legislation, the final result for the retired worker is the same: anguish in old age created, paradoxically, by the inherent insecurity of the “social security” system.

In 1980, the government of Chile decided to take the bull by the horns. A government-run pension system was replaced with a revolutionary innovation: a privately administered, national system of Pension Savings Accounts.

After 15 years of operation, the results speak for themselves. Pensions in the new private system already are 50 to 100 percent higher — depending on whether they are old-age, disability, or survivor pensions — than they were in the pay-as-you-go system. The resources administered by the private pension funds amount to $25 billion, or around 40 percent of GNP as of 1995. By improving the functioning of both the capital and the labor markets, pension privatization has been one of the key reforms that has pushed the growth rate of the economy upwards from the historical 3 percent a year to 6.5 percent on average during the last 12 years. It is also a fact that the Chilean savings rate has increased to 27 percent of GNP and the unemployment rate has decreased to 5.0 percent since the reform was undertaken.

More important, still, pensions have ceased to be a government issue, thus depoliticizing a huge sector of the economy and giving individuals more control over their own lives. The structural flaw has been eliminated and the future of pensions depends on individual behavior and market developments.

The success of the Chilean private pension system has led three other South American countries to follow suit. In recent years, Argentina (1994), Peru (1993), and Colombia (1994) undertook a similar reform. In the four South American countries, around 11 million workers have a personal retirement account.

The Chilean experience can be instructive to countries around the world. Even the United States is beginning to seriously debate privatizing its 60-year-old pension scheme. It should be noted that the U.S. Social Security system is the largest single government program in the world, spending more than $350 billion per year (more than the U.S. defense budget during the Cold War).

As an indication of the power of ideas, even officials from the People’s Republic of China have come to Chile to study the private pension system. One of the results is this particularly interesting feud reported recently by The Economist:

There is usually more acrimony than comedy in the long-running row between Britain and China over the future of Hong Kong. Yet a smile may have flickered across the face of Chris Patten, Hong Kong’s governor, even as China scuppered his plans to introduce a (pay-as-you-go) pension scheme in the colony. Zhou Nan, Communist China’s main representative in Hong Kong, harrumphed that Mr. Patten, a British conservative, was trying to bring “costly Euro-socialist” ideas to Hong Kong [11 February 1995].

It is possible that before entering the new millennium, several other countries, including all those in the Americas, will have privatized their pension system. This would mean a massive redistribution of power from the state to individuals, thus enhancing personal freedom, promoting faster economic growth, and alleviating poverty, especially in old age.

The Chilean PSA System

Under Chile’s Pension Savings Account (PSA) system, what determines a worker’s pension level is the amount of money he accumulates during his working years. Neither the worker nor the employer pays a social security tax to the state. Nor does the worker collect a government-funded pension. Instead, during his working life, he automatically has 10 percent of his wages deposited by his employer each month in his own, individual PSA. This percentage applies only to the first $22,000 of annual income. Therefore, as wages go up with economic growth, the “mandatory savings” content of the pension system goes down.

A worker may contribute an additional 10 percent of his wages each month, which is also deductible from taxable income, as a form of voluntary savings. Generally a worker will contribute more than 10 percent of his salary if he wants to retire early or obtain a higher pension.

A worker chooses one of the private Pension Fund Administration companies (“Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones,” AFPs) to manage his PSA. These companies can engage in no other activities and are subject to government regulation intended to guarantee a diversified and low-risk portfolio and to prevent theft or fraud. A separate government entity, a highly technical “AFP Superintendency,” provides oversight. Of course, there is free entry to the AFP industry.

Each AFP operates the equivalent of a mutual fund that invests in stocks and bonds. Investment decisions are made by the AFP. Government regulation sets only maximum percentage limits both for specific types of instruments and for the overall mix of the portfolio; and the spirit of the reform is that those regulations should be reduced constantly with the passage of time and as the AFP companies gain experience. There is no obligation whatsoever to invest in government or any other type of bonds. Legally, the AFP company and the mutual fund that it administers are two separate entities. Thus, should an AFP go under, the assets of the mutual fund — that is, the workers’ investments — are not affected.

Workers are free to change from one AFP company to another. For this reason there is competition among the companies to provide a higher return on investment, better customer service, or a lower commission. Each worker is given a PSA passbook and every three months receives a regular statement informing him how much money has been accumulated in his retirement account and how well his investment fund has performed. The account bears the worker’s name, is his property, and will be used to pay his old age pension (with a provision for survivors’ benefits).

As should be expected, individual preferences about old age differ as much as any other preferences. Some people want to work forever; others cannot wait to cease working and to indulge in their true vocations or hobbies, like writing or fishing. The old, pay-as-you-go system did not permit the satisfaction of such preferences, except through collective pressure to have, for example, an early retirement age for powerful political constituencies. It was a one-size-fits-all scheme that exacted a price in human happiness.

The PSA system, on the other hand, allows for individual preferences to be translated into individual decisions that will produce the desired outcome. In the branch offices of many AFPs, there are user-friendly computer terminals that permit the worker to calculate the expected value of his future pension, based on the money in his account, and the year in which he wishes to retire. Alternatively, the worker can specify the pension amount he hopes to receive and ask the computer how much he must deposit each month if he wants to retire at a given age. Once he gets the answer, he simply asks his employer to withdraw that new percentage from his salary. Of course, he can adjust that figure as time goes on, depending on the actual yield of his pension fund. The bottom line is that a worker can determine his desired pension and retirement age in the same way one can order a tailor-made suit.

As noted above, worker contributions are deductible for income tax purposes. The return on the PSA is tax free. Upon retirement, when funds are withdrawn, taxes are paid according to the income tax bracket at that moment.

The Chilean PSA system includes both private and public sector employees. The only ones excluded are members of the police and armed forces, whose pension systems, as in other countries, are built into their pay and working conditions system. (In my opinion–but not yet theirs — they would also be better off with a PSA). All other employed workers must have a PSA. Self-employed workers may enter the system, if they wish, thus creating an incentive for informal workers to join the formal economy.

A worker who has contributed for at least 20 years but whose pension fund, upon reaching retirement age, is below the legally defined “minimum pension” receives that pension from the state once his PSA has been depleted. What should be stressed here is that no one is defined as “poor” a priori. Only a posteriori, after his working life has ended and his PSA has been depleted, does a poor pensioner receive a government subsidy. (Those without 20 years of contributions can apply for a welfare-type pension at a much lower level.)

The PSA system also includes insurance against premature death and disability. Each AFP provides this service to its clients by taking out group life and disability coverage from private life insurance companies. This coverage is paid for by an additional worker contribution of around 2.9 percent of salary, which includes the commission to the AFP.

The mandatory minimum savings level of 10 percent was calculated on the assumption of a 4 percent average net yield during the whole working life, so that the typical worker would have sufficient money in his PSA to fund a pension equal to 70 percent of his final salary.

The so-called legal retirement age is 65 for men and 60 for women. Those retirement ages — the traditional ages in the pay-as-you-go system — were not discussed in the privatization reform because they are not a structural characteristic of the new system. But the meaning of “retirement” in the PSA system is different than in the traditional one. First, workers can continue working after retirement. If they do, they receive the pension their accumulated capital makes possible and they are not required to contribute any longer to a pension plan. Second, workers with sufficient savings in their accounts to fund a “reasonable pension” (50 percent of the average salary of the previous 10 years, as long as it is higher than the “minimum pension”) may choose to take early retirement whenever they want.

Thus, the 65-60 threshold is not a rigid fixture of the system. Rather, a worker must continue making a 10 percent contribution to his PSA until he reaches that age, unless he has chosen early retirement–that is, to retire his money, as a monthly pension, which is not the same as retirement from the workforce. In addition, however, a worker must reach those threshold ages to be eligible for the government subsidy that guarantees a minimum pension.

But in no way is there an obligation to cease working, at any age, nor is there an obligation to continue working or saving for pension purposes once you have assured yourself a “reasonable pension” as described above.

Upon retiring, a worker may choose from two general payout options. In one case, a retiree may use the capital in his PSA to purchase an annuity from any private life insurance company. The annuity guarantees a constant monthly income for life, indexed to inflation (there are indexed bonds available in the Chilean capital market so that companies can invest accordingly), plus survivors’ benefits for the worker’s dependents. Alternatively, a retiree may leave his funds in the PSA and make programmed withdrawals, subject to limits based on the life expectancy of the retiree and his dependents. In the latter case, if he dies, the remaining funds in his account form a part of his estate. In both cases, he can withdraw as a lump-sum the capital in excess of that needed to obtain an annuity or programmed withdrawal equal to 70 percent of his last wages.

The PSA system solves the typical problem of pay-as-you-go systems with respect to labor demographics: in an aging population the number of workers per retiree decreases. Under the PSA system, the working population does not pay for the retired population. Thus, in contrast with the pay-as-you-go system, the potential for inter-generational conflict and eventual bankruptcy is avoided. The problem that many countries face — unfunded pension liabilities — does not exist under the PSA system.

In contrast to company-based private pension systems that generally impose costs on workers who leave before a given number of years and that sometimes result in bankruptcy of the workers’ pension funds — thus depriving workers of both their jobs and their pension rights — the PSA system is completely independent of the company employing the worker. Since the PSA is tied to the worker, not the company, the account is fully portable. Given that the pension funds must be invested in tradeable securities, the PSA has a daily value and therefore is easy to transfer from one AFP to another. The problem of “job lock” is entirely avoided. By not impinging on labor mobility, both inside a country and internationally, the PSA system helps create labor market flexibility and neither subsidizes nor penalizes immigrants.

A PSA system is also much more efficient in promoting a flexible labor market. In fact, people are increasingly deciding to work only a few hours a day or to interrupt their working lives — especially women and young people. In pay-as-you-go systems, those flexible working styles create the problem of filling the gaps in contributions. Not so in a PSA scheme where stop-and-go contributions are no problem whatsoever.

The Transition

One challenge is to define the permanent PSA system. Another, in countries that already have a pay-as-you-go system, is to manage the transition to a PSA system. The transition has to take into account the particular characteristics of each country, of course, especially constraints posed by the budget situation.

In Chile we set three basic rules for the transition:

- The government guaranteed those already receiving a pension that their pensions would be unaffected by the reform. This rule was important because the social security authority would obviously cease to receive the contributions from the workers who moved to the new system. Therefore the authority would be unable to continue paying pensioners with its own resources. Moreover, it would be unfair to the elderly to change their benefits or expectations at this point in their lives.

- Every worker already contributing to the pay-as-you-go system was given the choice of staying in that system or moving to the new PSA system. Those who left the old system were given a “recognition bond” that was deposited in their new PSAs. (The bond was indexed and carried a 4 percent real interest rate.) The government pays the bond only when the worker reaches the legal retirement age. The bonds are traded in secondary markets, so as to allow them to be used for early retirement. This bond reflected the rights the worker had already acquired in the pay-as-you-go system. Thus, a worker who had made pension contributions for years did not have to start at zero when he entered the new system.

- All new entrants to the labor force were required to enter the PSA system. The door was closed to the pay-as-you-go system because it was unsustainable. This requirement assured the complete end of the old system once the last worker who remained in it reaches retirement age (from then on, and for a limited period of time, the government has only to pay pensions to retirees of the old system). This rule is important because the most effective way to reduce the size of the government in our lives is to end programs completely, not simply scale them back so that a new government might revive them at a later date.

After several months of national debate on the proposed reforms, and a communication and education effort to explain the reform to the people,[1] the pension reform law was approved on November 4, 1980.

To give equal access to creating AFPs to all those who might be interested, the law established a six-month period during which no AFP could begin operations (not even advertising). Thus, the AFP industry is unique in that it had a clear day of conception (November 4, 1980) and a clear date of birth (May 1, 1981).

In Chile, as in most countries (but not the United States), May 1 is Labor Day. The choice of that date was not a coincidence. Symbols are important, and that date of birth allows workers to celebrate May 1 not as a day of class struggle but as the day when they were freed to choose their own pension system and thus freed from “the chains” of the state-run social security system.

Together with the creation of the new AFP system, all gross wages were redefined to include most of the employer’s contribution to the old pension system. (The rest of the employer’s contribution was turned into a transitory tax on the use of labor to help the financing of the transition; once that tax was completely phased out, as established in the pension reform law, the cost to the employer of hiring workers decreased.) The worker’s contribution was deducted from the increased gross wage. Because the total contribution was lower in the new system than in the old, net salaries for those who moved to the new system increased by around 5 percent.

In that way, we ended the illusion that both the employer and the worker contribute to social security, a device that allows political manipulation of those rates. From an economic standpoint, workers bear nearly the full burden of the payroll tax because the aggregate supply of labor is highly inelastic. Also, all the contributions are ultimately paid from the worker’s marginal productivity, and employers must take into account all labor costs — whether termed salary or social security contributions–in making their hiring and pay decisions. By renaming the employer’s contribution, the system makes it evident that all contributions are made by the worker. In this scenario, of course, the final wage level is determined by the interplay of market forces.

The financing of the transition is a complex technical issue and each country must address this problem according to its own circumstances. The implicit pay-as-you-go debt of the Chilean system in 1980 has been estimated at around 80 percent of GDP.[2] (The value of that debt had been reduced by a reform of the old system in 1978, especially by the rationalization of indexing, the elimination of special regimes, and the raising of the retirement age.)

A recent World Bank study (1994: 268) stated that “Chile shows that a country with a reasonably competitive banking system, a well-functioning debt market, and a fair degree of macroeconomic stability can finance large transition deficits without large interest rate repercussions.”

Chile used five methods to finance the short-run fiscal costs of changing to a PSA system:

- In the state’s balance sheet (in which each government should show its assets and liabilities), state pension obligations were offset to some extent by the value of state-owned enterprises and other types of assets. Therefore, privatization was not only one way to finance the transition but had several additional benefits such as increasing efficiency, spreading ownership, and depoliticizing the economy.

- Since the contribution needed in a capitalization system to finance adequate pension levels is generally lower than the current payroll taxes, a fraction of the difference between them can be used as a temporary transition tax without reducing net wages or increasing the cost of labor to the employer.

- Using debt, the transition cost can be shared by future generations. In Chile, roughly 40 percent of the cost has been financed by issuing government bonds at market rates of interest. These bonds have been bought mainly by the AFPs as part of their investment portfolios and that “bridge debt” should be completely redeemed when the pensioners of the old system are no longer with us (a source of sadness to their families and friends, but, undoubtedly, a source of relief to future ministers of finance).

- The need to finance the transition was a powerful incentive to reduce wasteful government spending. For years, the budget director has been able to use this argument to kill unjustified new spending or to reduce wasteful government programs.

- The increased economic growth that the PSA system promoted substantially increased tax revenues, especially those from the value-added tax. Only 15 years after the pension reform, Chile is running fiscal budget surpluses.

The Results

The PSAs have already accumulated an investment fund of $25 billion, an unusually large pool of internally generated capital for a developing country of 14 million people and a GDP of $60 billion.

This long-term investment capital has not only helped fund economic growth but has spurred the development of efficient financial markets and institutions. The decision to create the PSA system first, and then privatize the large state-owned companies second, resulted in a “virtuous sequence.” It gave workers the possibility of benefiting handsomely from the enormous increase in productivity of the privatized companies by allowing workers, through higher stock prices that increased the yield of their PSAs, to capture a large share of the wealth created by the privatization process.

There are around 15 AFP companies and they are a diverse group. Some belong to insurance or banking conglomerates. Others are worker-owned or tied to labor unions or specific industry or trade associations. Some include the participation of international financial companies, such as AIG, Aetna, and Banco de Santander. Several of the larger AFP companies are themselves publicly traded on the Chilean stock exchange, and one of them recently issued American depository receipts on Wall Street (helped by the recent “A-” credit rating of Chilean sovereign bonds).

One of the key results of the new system has been to increase the productivity of capital and thus the rate of economic growth in the Chilean economy. The PSA system has made the capital market more efficient and influenced its growth over the past 15 years. The vast resources administered by the AFPs have encouraged the creation of new kinds of financial instruments while enhancing others already in existence but not fully developed. Another of Chile’s pension reform contributions to the sound operation and transparency of the capital market has been the creation of a domestic risk-rating industry and the improvement of corporate governance. (The AFPs appoint outside directors in the companies in which they own shares, thus shattering complacency at board meetings.)

Since the system began to operate on May 1, 1981, the average real return on investment has been 13 percent per year (more than three times higher than the anticipated yield of 4 percent). Of course, the annual yield has shown the oscillations that are intrinsic to the free market — ranging from minus 3 percent to plus 30 percent in real terms — but the important yield is the average one over the long term.

Pensions under the new system have been significantly higher than under the old, state-administered system, which required a total payroll tax of around 25 percent. According to a recent study by Sergio Baeza (1995), the average AFP retiree is receiving a pension equal to 78 percent of his mean annual income over the previous 10 years of his working life. As mentioned, upon retirement workers may withdraw in a lump sum their “excess savings” (above the 70 percent of salary threshold). If that money were included in calculating the value of the pension, the total value would come close to 84 percent of working income. Recipients of disability pensions also receive, on average, 70 percent of their working income.

The new pension system, therefore, has made a significant contribution to the reduction of poverty by increasing the size and certainty of old-age, survivors, and disability pensions, and by the indirect but very powerful effect of promoting economic growth and employment.

The new system also has eliminated the unfairness of the old system. According to conventional wisdom, pay-as-you-go pension schemes redistribute income from the rich to the poor. However, recent studies have shown that once certain income-specific characteristics of workers and of the operation of the political system are taken into account, public schemes generally redistribute income to the rich — and especially to the most powerful groups of workers.[3]

Conclusion

It is not surprising that the PSA system in Chile has proven so popular and has helped promote social and economic stability. Workers appreciate the fairness of the system and they have obtained through their pension accounts a direct and visible stake in the economy. Since the private pension funds own a sizable fraction of the stocks of the biggest companies of Chile, workers are actually investors in the country’s fortunes.

When the PSA was inaugurated in Chile in 1981, workers were given the choice of entering the new system or remaining in the old one. Half a million Chilean workers (one fourth of the eligible workforce) chose the new system by joining in the first month of operation alone — far more than the 50,000 that had been expected. Today, more than 90 percent of Chilean workers who had been under the old system are in the new system. By 1995, 5 million Chileans had PSA accounts, although not all belonged to active, full-time workers, and therefore not all contribute in any given month.

The bottom line is that when given a choice, workers vote with their money overwhelmingly for the free market — even when it comes to such “sacred cows” as social security.

As the state pension system disappears, politicians will no longer decide whether pension checks need to be increased and in what amount or for which groups. Thus, pensions are no longer a key source of political conflict and election-time demagoguery as they once were. A person’s retirement income will depend on his own work and on the success of the economy, not on the government or on the pressures brought by special interest groups.

For Chileans, pension savings accounts now represent real and visible property rights — they are the primary sources of security for retirement. After 15 years of operation of the new system, in fact, the typical Chilean worker’s main asset is not his used car or even his small house (probably still mortgaged), but the capital in his PSA.

Finally, the private pension system has had a very important political and cultural consequence. The overwhelming majority of Chilean workers who chose to move into the new system moved into it faster than Germans going from East to West after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Those workers freely decided to abandon the state system even though some of the national trade-union leaders and the old political class advised against it. Workers care deeply about matters close to their lives, such as pensions, education, and health, and make their decisions thinking about their families and not according to political fashions.

Indeed, the new pension system gives Chileans a personal stake in the economy. A typical Chilean worker is not indifferent to the behavior of the stock market or interest rates. Intuitively he knows that a bad minister of finance can reduce the value of his pension rights. When workers feel that they own a part of the country, not through party bosses or a Politburo, they are much more attached to the free market and a free society.

This is a brief story of a dream that has come true. The ultimate lesson is that the only revolutions that are successful are those that trust the individual, and the wonders that individuals can do when they are free.

* José Piñera is President of the International Center for Pension Reform and Co-Chairman of the Cato Project on Social Security Privatization. As Minister of Labor and Social Security from 1978 to 1980, he was responsible for the privatization of the Chilean pension system. This paper is based on a presentation made at the Mont Pelerin Society’s regional meeting in Cancun, Mexico, January 17, 1996. The author wishes to thank Edward H. Crane for helpful comments.

Arizona? Inside Mexico, Illegal Aliens Get No Breaks

Arizona? Inside Mexico, Illegal Aliens Get No Breaks – by Michelle Malkin

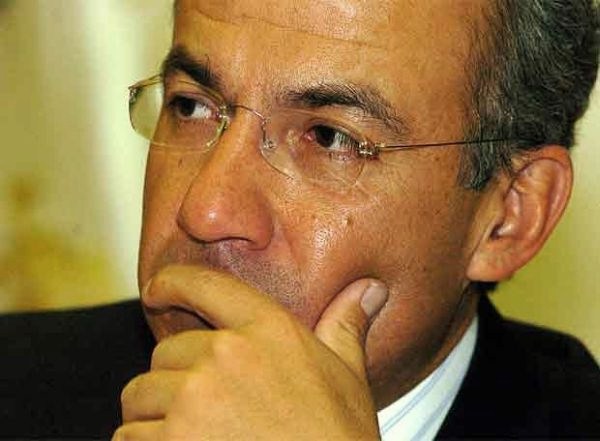

Mexican President Felipe Calderon has accused Arizona of opening the door “to intolerance, hate, discrimination and abuse in law enforcement.” But Arizona has nothing on Mexico when it comes to cracking down on illegal aliens.

Mexican President Felipe Calderon has accused Arizona of opening the door “to intolerance, hate, discrimination and abuse in law enforcement.” But Arizona has nothing on Mexico when it comes to cracking down on illegal aliens.

As open-borders activists decry new enforcement measures in “Nazi-zona,” they remain deaf, dumb or willfully blind to the unapologetically restrictionist policies of our neighbors to the south.

The Arizona law bans sanctuary cities that refuse to enforce immigration laws, stiffens penalties against illegal alien day laborers and their employers, makes it a misdemeanor for immigrants to fail to carry an alien registration document and allows the police to arrest immigrants unable to show documents proving they’re here legally.

If those rules constitute the racist, fascist, xenophobic, inhumane regime that the National Council of La Raza, Al Sharpton, Catholic bishops and their grievance-mongering followers claim, what about these rules and restrictions imposed on foreigners?

• The Mexican government will bar foreigners if they upset “the equilibrium of the national demographics.” How’s that for racial and ethnic profiling?

• If outsiders do not enhance the country’s “economic or national interests” or are “not found to be physically or mentally healthy,” they are not welcome. Neither are those who show “contempt against national sovereignty or security.” They must not be economic burdens on society and must have clean criminal histories.

Those seeking to obtain Mexican citizenship must show a birth certificate, provide a bank statement proving economic independence, pass an exam and prove that they can provide their own health care.

• Illegal entry into the country is equivalent to a felony punishable by two years’ imprisonment. Document fraud is subject to fine and imprisonment; so is alien marriage fraud. Evading deportation is a serious crime; illegal re-entry after deportation is punishable by 10 years’ imprisonment.

Foreigners may be kicked out of the country without due process and the endless bites at the litigation apple that illegal aliens are afforded in our country.

• Officials at all levels must cooperate to enforce immigration laws, including illegal alien arrests and deportations. The Mexican military is also required to assist in immigration enforcement operations. Native-born Mexicans are empowered to make citizen’s arrests of illegal aliens.

• Ready to show your papers? Mexico’s National Catalog of Foreigners tracks all outside tourists and foreign nationals. A National Population Registry tracks and verifies the identity of every member of the population, who must carry a citizen’s identity card. Visitors who do not possess proper documents and identification are subject to arrest as illegal aliens.

All these provisions are enshrined in Mexico’s Ley General de Poblacion (General Law of the Population) and were spotlighted in a 2006 research paper published by the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Security Policy. There’s been no clamor for “comprehensive immigration reform” in Mexico, however, because pro-illegal-alien speech by outsiders is prohibited.

Consider: Open-borders protesters marched freely at the Capitol building in Arizona, comparing GOP Gov. Jan Brewer to Hitler, waving Mexican flags, advocating that demonstrators “Smash the State” and holding signs that proclaimed “No human is illegal” and “We have rights.”

But under the Mexican constitution, such political speech by foreigners is banned. Noncitizens cannot “in any way participate in the political affairs of the country.” In fact, a plethora of Mexican statutes enacted by its congress limit the participation of foreign nationals and companies in everything from investment, education, mining and civil aviation to electric energy and firearms. Foreigners have severely limited private property and employment rights.

As for abuse, the Mexican government is notorious for its abuse of Central American illegal aliens who attempt to violate Mexico’s southern border. The Red Cross has protested rampant Mexican police corruption, intimidation and bribery schemes targeting illegal aliens there for years.

Mexico didn’t respond by granting mass amnesty to illegal aliens, as it’s demanding we do. It tightened its borders even more. In late 2008, the Mexican government launched an aggressive deportation plan to curtain illegal Cuban immigration and human trafficking through Cancun.

Meanwhile, Mexican consular offices in the U.S. have coordinated with left-wing social justice groups and the Catholic Church leadership to demand a moratorium on all deportations and a freeze on all employment raids across America.

Mexico is doing the job Arizona is now doing — a job the U.S. government has failed miserably to do: put its people first. Here’s the proper rejoinder to all the hysterical demagogues calling for boycotts and invoking Jim Crow laws, apartheid and the Holocaust because Arizona has taken its sovereignty into its own hands: Hipocritas.

US: Clueless on immigration –

US: Clueless on immigration – by Ruben Navarrette Jr.

Just in time for Cinco de Mayo – or as President Barack Obama mistakenly referred to it at a White House reception last year marking the Mexican holiday, “Cinco de Cuatro” – the chief executive is delivering a clear message to the nation’s embattled Latino community: “You’re on your own, amigos.”

Just in time for Cinco de Mayo – or as President Barack Obama mistakenly referred to it at a White House reception last year marking the Mexican holiday, “Cinco de Cuatro” – the chief executive is delivering a clear message to the nation’s embattled Latino community: “You’re on your own, amigos.”

The nicest thing you can say is that Obama is failing to deal with one of the great moral issues of our time: immigration reform. The not-so-nice version is that Obama is subverting the immigration reform cause to get congressional Democrats off the hook in an election year when their prospects are shaky.

Latino Democrats have been telling themselves that the reason Obama broke his campaign promise to work for immigration reform in his first year is because he had a full plate of other issues. They swallowed every disappointment – when the administration kept up the policy of raiding workplaces, when Obama dedicated just 37 words to immigration in his State of the Union address, when it was revealed that Immigration and Customs Enforcement uses quotas to ratchet up the number of deportations.

In the latest setback, activists are quietly fuming that Obama couldn’t summon a stronger word than “misguided” to describe Arizona’s racial profiling law – something for which The New York Times editorial page also took Obama to task.

Why would this surprise anyone? Obama has a poor record on immigration. As a senator, he joined Democratic leader Harry Reid in trying to kill an immigration reform bill with poison pill amendments – all to please organized labor, which preferred no bill to one with guest workers.

Obama has also been more than willing to play politics with the immigration issue for short-term gain. My theory is that Obama falls into the part of the liberal spectrum that is leery of immigration reform because of concerns that immigrant labor hurts blue-collar workers, especially African-Americans.

Now, a line has been crossed. On Air Force One a few days ago, Obama went from not helping the cause of comprehensive immigration reform to actually hurting it. In a rare visit to the press section of the plane, Obama threw cold water on the prospect of Congress overhauling immigration laws this year – and in doing so, cut the legs out from underneath immigration reform proponents.

Submitting that “there may not be an appetite” to repair the broken immigration system this year, Obama tried to portray Republicans as the problem. Forget that Democrats run the show at both ends of PennsylvaniaAvenue. Obama claimed that he needs Republican votes to pass immigration reform, and, rather than go it alone with only Democratic support, he’s willing to wait for GOP lawmakers.

Good luck. Obama knows full well that the Republicans won’t help him cross the street until after November. Besides, where was this insistence on waiting for Republican support when the cause was health care reform?

There, the president forged ahead without the GOP.

Mr. President, you picked a fine time to go AWOL. The enactment of the Arizona racial profiling law, which subjects Latinos to second-class treatment and harassment, makes it vital that the White House and Congress take on the immigration issue in order to provide illegal immigrants with a federal cloak of protection against abuses in Arizona.

This looks familiar. Numerous historians have noted that John F. Kennedy was no friend to the civil rights movement early in his presidency because he worried it would torpedo his legislative agenda. He even ordered Attorney General Robert Kennedy to try to convince activists to forgo the freedom rides that challenged Jim Crow laws in the South. It wasn’t until May 1963, when television brought into American homes the disturbing images of police dogs and fire hoses being turned on demonstrators in Birmingham, Ala., that Kennedy finally started coming around. On June 11, 1963, the president – in a national address broadcast on radio and television – described civil rights as “a moral issue … as old as the Scriptures and … as clear as the American Constitution.”

Better late than never. For a time, Kennedy was, by virtue of his life experience, clueless when it came to the issue of civil rights. Now Obama is making similar mistakes because he is just as clueless about immigration.

US: Keeping up with the Jones Act

US: Keeping up with the Jones Act – by Deroy Murdock

As a self-proclaimed “citizen of the world,” President Obama should have welcomed rather than spurned international assistance to prevent BP’s underwater oil geyser from wrecking the Gulf Coast. But spurn, he did. Mr. Obama’s failure to waive the Jones Act still maintains a sea wall that blocks potentially helpful foreign ships from this tear-inducing mess.

As a self-proclaimed “citizen of the world,” President Obama should have welcomed rather than spurned international assistance to prevent BP’s underwater oil geyser from wrecking the Gulf Coast. But spurn, he did. Mr. Obama’s failure to waive the Jones Act still maintains a sea wall that blocks potentially helpful foreign ships from this tear-inducing mess.

The 1920 Jones Act requires that vessels operating in American waters be built, owned and manned by Americans. Some U.S. ship owners love this protectionist measure. So do maritime labor unions. When it comes to confronting unions, Mr. Obama rarely crosses that line.

On April 20, the Deepwater Horizon exploded, killed 11 oil rig workers, and began gushing perhaps 60,000 barrels of petroleum daily. Three days later, the Dutch offered to sail to the rescue on ships bedecked with oil-skimming booms. They also had a plan for erecting protective sand barricades.

“The embassy got a nice letter from the administration that said, ‘Thanks, but no thanks,’ ” Dutch consul general Geert Visser told the Houston Chronicle’s Loren Steffy. Had those Dutch ships departed nearly two months ago, who knows how much oil they already would have absorbed and how many pelicans now would soar rather than soak in soapy water while wildlife experts clean their wings.

After initially refusing to name them, the State Department on May 5 declared that 11 other countries and the United Nations also had offered skimmer boats and other assets and experts to prevent the oil from destroying dolphins, crabs, oysters and this disaster’s other defenseless victims.

Alas, they were turned away.

“While there is no need right now that the U.S. cannot meet,” stated a State Department statement, “the U.S. Coast Guard is assessing these offers of assistance to see if there will be something which we will need in the near future.” Foreign Policy’s Josh Rogin translated this into plain English: “The current message to foreign governments is: Thanks but no thanks, we’ve got it covered.”

Had Mr. Obama instead waived the Jones Act via executive order – as did President George W. Bush three days after Hurricane Katrina – that S.O.S. would have summoned a global armada of mercy. Who knows how many fishing, shrimping and seafood-processing jobs this would have saved? Instead, thousands of Gulf Coast workers will endure a long march from dormant docks to bustling unemployment lines.

Even now, Mr. Obama could invite the world to send boats to clean the waters off Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida and (potentially) the Carolinas and points north, if this mass of oil (so far, roughly equal to 13 Exxon Valdez oil spills) enters the Loop Current, swerves around Key West, slips into the Gulf Stream, and slides up the Eastern Seaboard.

“If there is the need for any type of waiver, that would obviously be granted,” White House spokesman Robert Gibbs promised on June 10. “But, we’ve not had that problem thus far in the Gulf.”

Problem? What problem?

The Jones Act sometimes gets waived. As Fox News Channel’s Brian Wilson reported on June 11: “A U.S. Customs official ruled recently that the Jones Act does not apply to foreign-owned vessels installing wind turbines off the coast of Delaware.”

Watching Mr. Obama’s Tuesday night Oval Office address, BP’s brass must have been startled to hear the president say: “I will meet with the chairman of BP and inform him that he is to set aside whatever resources are required to compensate the workers and business owners who have been harmed as a result of his company’s recklessness.”

Should BP pay, and pay big? Yes.

Reckless? BP sure seems so.

But since when does the American president “inform” executives that they must devote billions to any cause, no matter how worthy? Isn’t this why Congress passes legislation and courts administer justice?

So, while a pro-labor trade barrier traps potentially helpful boats in overseas ports, due process withers under presidential diktat.

And the crude oil keeps on flowing.

* Deroy Murdock is a nationally syndicated columnist with the Scripps Howard News Service.

Venezuela: Rotten food containers continue to appear nationwide

Venezuela: Rotten food containers continue to appear nationwide – El Universal

Government blames private sector over politicization of food security

Carlos Osorio, the National Superintendent of Silos, Warehouse and Agricultural Storage (SADA), blamed the private sector for considering food processing plants as a “machine to make money,” while the government sees them as a matter of security.

He urged the private sector, which previously controlled the distribution of food, to ensure the people’s access to products rather than using them “as a tool to make politics.”

He said that in the past food distribution was in private hands. However, since 2002 the Venezuelan government has implemented several tasks and penalties to stabilize the agrifood policy, to the extent that it already has a large infrastructure to balance the distribution of products.

June 16

Venezuelan ship with spoiled food for Haiti is anchored in Puerto Cabello

Members of the staff of the Puerto Cabello Ports Authority confirmed the presence of Santa Paula, a ship with the Venezuelan flag, which was returned to Venezuela by authorities of the Dominican Republic, where the ship had been sent with a shipment of spoiled food to aid Haiti.

According to the reports, the ship is anchored in the C area of the docks. The entry date was June 6. Sources have said that some containers have been unloaded.

The Venezuelan ship was returned from Dominican Republic because the containers with humanitarian aid sent to Haiti had rotten food.

Members of the staff of Bolipuertos who work in the primary area of the docks have said that the ship arrived at the shipping terminal a few days ago. The vessel brought back 68 containers with approximately 39 tons of rotten food.

June 17

Town councillor reports loss of 1,600 tons of rice in Carabobo

A new cargo of spoiled food would have been located in a warehouse in Puerto Cabello, as reported on June 16 by Ylidio Abreu, a town councillor of Puerto Cabello municipality.

The government official added that the authorities had found 1,600 tons of rotten rice “that could have been used to give one kilogram of rice to each inhabitant of the state.”

Abreu said that the huge amount of rice had been abandoned 18 months ago in a warehouse near the port facilities. He said that according to a report issued by the Municipal Institute for Environmental Protection, the food has bacterial spores, fungi and mycotoxins.

Meanwhile, a group of officials of the Bolivarian Intelligence Service (Sebin) raided the house of Yara Margarita Aguilera, who was the former customs manager of the state-run food distribution network Pdval in the region until the first week of May 2010, when she disclosed the discovery of 1,197 containers with spoiled food.

Moreover, officials from the Puerto Cabello Ports Authority said that the ship named Santa Paula, owned by the ship’s company Buques del Alba, is still anchored in the bay of Puerto Cabello.

June 18

Ruling party’s governor admits existence of rotten food in his state

Anzoátegui state governor Tarek William Saab admitted that there is rotten food in the industrial port of Jose.

The pro-government governor said that the shipment of powdered milk that arrived in the industrial port had already expired and it was the result of a deal between a Chinese company and the state-run food distribution network Pdval, the private TV news network Globovisión reported.

The governor promised to review all the documents and file charges against the Chinese importer.

Venezuela denies having sent ship with spoiled food to Haiti

The Venezuelan government denied on June 18 that the vessel with food containers sent to Haiti last January was returned to the country because the products were rotten and clarified that the decision was taken precisely to avoid food decay.

In a press release issued by the Ministry of Food, the government “denies” reports about the “return of 51 containers allegedly with spoiled food” that were sent as part of humanitarian aid to the Caribbean island, devastated by an earthquake in January.

According to the authorities, Venezuela “requested the return of the containers to the country to avoid the expiration of food,” after assessing “prevailing conditions in Haiti.”

The 51 containers were part of a group of 224 containers, “of which 173 arrived at its destination without any problem,” said the press release.

Guns Save Lives

Guns Save Lives – by John Stossel

You know what the mainstream media think about guns and our freedom to carry them.

You know what the mainstream media think about guns and our freedom to carry them.

Pierre Thomas of ABC: “When someone gets angry or when they snap, they are going to be able to have access to weapons.”

Chris Matthews of MSNBC: “I wonder if in a free society violence is always going to be a part of it if guns are available.”

Keith Olbermann, who usually can’t be topped for absurdity: “Organizations like the NRA … are trying to increase deaths by gun in this country.”

“Trying to?” Well, I admit that I bought that nonsense for years. Living in Manhattan, working at ABC, everyone agreed that guns are evil. And that the NRA is evil. (Now that the NRA has agreed to a sleazy deal with congressional Democrats on political speech censorship, maybe some of its leaders are evil, but that’s for another column.)

Now I know that I was totally wrong about guns. Now I know that more guns means — hold onto your seat – less crime.

How can that be, when guns kill almost 30,000 Americans a year? Because while we hear about the murders and accidents, we don’t often hear about the crimes stopped because would-be victims showed a gun and scared criminals away. Those thwarted crimes and lives saved usually aren’t reported to police (sometimes for fear the gun will be confiscated), and when they are reported, the media tend to ignore them. No bang, no news.

This state of affairs produces a distorted public impression of guns. If you only hear about the crimes and accidents, and never about lives saved, you might think gun ownership is folly.

But, hey, if guns save lives, it logically follows that gun laws cost lives.

Suzanna Hupp and her parents were having lunch at Luby’s cafeteria in Killeen, Texas, when a man began shooting diners with his handgun, even stopping to reload. Suzanna’s parents were two of the 23 people killed. (Twenty more were wounded.)

Suzanna owned a handgun, but because Texas law at the time did not permit her to carry it with her, she left it in her car. She’s confident that she could have stopped the shooting spree if she had her gun. (Texas has since changed its law.)

Today, 40 states issue permits to competent, law-abiding adults to carry concealed handguns (Vermont and Alaska have the most libertarian approach: no permit needed. Arizona is about to join that exclusive club.) Every time a carry law was debated, anti-gun activists predicted outbreaks of gun violence after fender-benders, card games and domestic quarrels.

What happened?

John Lott, in “More Guns, Less Crime,” explains that crime fell by 10 percent in the year after the laws were passed. A reason for the drop in crime may have been that criminals suddenly worried that their next victim might be armed. Indeed, criminals in states with high civilian gun ownership were the most worried about encountering armed victims.

In Canada and Britain, both with tough gun-control laws, almost half of all burglaries occur when residents are home. But in the United States, where many households contain guns, only 13 percent of burglaries happen when someone_s at home.

Two years ago, the Supreme Court ruled in the Heller case that Washington, D.C.’s ban on handgun ownership was unconstitutional. District politicians then loosened the law but still have so many restrictions that there are no gun shops in the city and just 800 people have received permits. Nevertheless, contrary to the mayor’s prediction, robbery and other violent crime are down.

Because Heller applied only to Washington, that case was not the big one. McDonald v. Chicago is the big one, and the Supreme Court is expected to rule on that next week. Otis McDonald is a 76-year-old man who lives in a dangerous neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. He wants to buy a handgun, but Chicago forbids it.

If the Supremes say McDonald has that right, then restrictive gun laws will fall throughout America.

Despite my earlier bias, I now understand that striking down those laws will probably save lives.

* John Stossel is host of “Stossel” on the Fox Business Network. He’s the author of “Give Me a Break” and of “Myth, Lies, and Downright Stupidity.” To find out more about John Stossel, visit his site at >johnstossel.com.

Economic Freedom in the “Bolivarian Andes” Is Melting Away

Economic Freedom in the “Bolivarian Andes” Is Melting Away

by James RobertsAbstract: In the past, “Bolivarian” referred to those Andean countries that had been liberated by Simón Bolívar. Today, for the three countries in the Andes that are following Hugo Chávez’s “Bolivarian Alternative” path— Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela—it has come to signify declining economic freedom. A closer look at those countries’ scores on the 10 indicators in The Heritage Foundation’s 2010Index of Economic Freedom will shed light on exactly how and why their economies are failing to deliver the prosperity that their populist leaders have repeatedly promised and failed to deliver. The performance of market-friendly and democratic countries such as Peru, Colombia, and long-time Latin American economic freedom leader Chile is proving that Andean governments can deliver true economic and political freedom to their citizens if leaders govern with the correct mix of policies favoring private property, rule of law, and market-based democratic institutions.

There is dramatic news in the 2010 edition of The Heritage Foundation’s annual Index of Economic Freedom: For the first time, the United States has dropped from “free” to only “mostly free” and the United Kingdom has dropped out of the top ten. What is less shocking, however, is that the Index scores for the three countries in the Andes that are following Hugo Chávez’s “Bolivarian Alternative” path—Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela—continue to plunge. In the past, “Bolivarian” referred to those Andean countries that had been liberated by Simón Bolívar. Today, it has come to signify declining economic freedom.

While it is not surprising, it is sad that the leaders of those countries—Presidents Evo Morales, Rafael Correa, and Hugo Chávez, respectively—as well as the people who support them do not seem to realize that their statist “Bolivarian” policies are doomed to failure. A closer look at those countries’ scores on the 10 indicators in the Index when compared to the only successful economies in the Andes—Peru, Colombia, and especially Chile—will shed light on exactly how and why their economies are failing to deliver the prosperity that their populist leaders have repeatedly promised and failed to deliver.

Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela are among the worst performing countries in the 2010 Index in all of Latin America. Several of the other poor performers in the region—such as Cuba and Nicaragua— are also governed by statist regimes. Meanwhile, the performance of market-friendly and democratic countries such as Peru, Colombia (the most improved country regionally in the 2010 Index), and long-time Latin American economic freedom leader Chile are proving that Andean governments can deliver true economic and political freedom to their citizens if leaders govern with the correct mix of policies favoring private property, rule of law, and market-based democratic institutions.

Chart 1 shows these diverging performances graphically. Chile has scored highest throughout the period, while Colombia’s score has improved steadily in reflection of the tough economic reform measures implemented by President Álvaro Uribe over the past half-decade. Meanwhile, all three Bolivarian countries in the Andes have registered a progressively downward trend in their scores and now sit at the bottom of the rankings—both in their own region and among worldwide Index scores.

A common pattern among the three Bolivarian countries is that they all suffer from institutional weakness and do not have clearly established rules of the game. All three countries have recently adopted new constitutions that concentrate power in the executive and favor government intervention in the economy. This does not incentivize any entrepreneur to prosper and generate prosperity for others. A deeper look at each of the Bolivarian countries’ scores reveals the failures they have in common and how they differ from economic freedom leader Chile. The statist policy errors they share have resulted in exceptionally low scores on the indicators shown in Table 1.

Bolivia (146th out of 179 Ranked Countries)